One-third of residents across the Greater Washington region experienced some level of food insecurity in 2021, according to findings from a first-of-its-kind general population survey on food insecurity and inequity conducted by the Capital Area Food Bank and NORC at the University of Chicago.

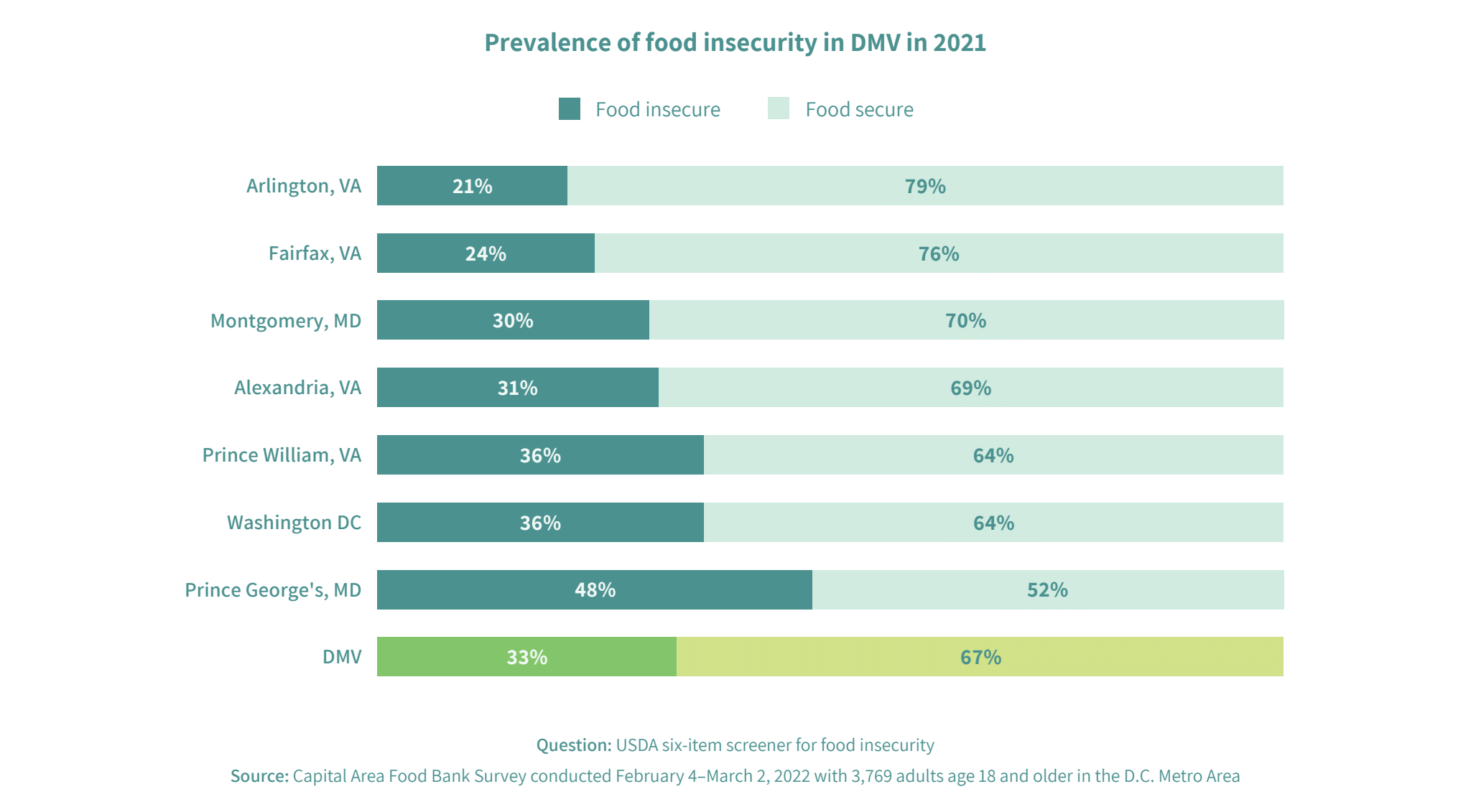

That overall rate means that more than 1.2 million people across the region didn’t know where their next meal was coming from at some point during 2021. In some counties, nearly half of all residents experienced food insecurity at some point last year. In every county, at least one in five people faced challenges getting enough to eat.

- Nearly half – 48% — of the residents of Prince George’s County, Md., faced food insecurity.

- In Prince William County, Va., and Washington, DC, 36% of residents were affected.

The breathtaking findings in our new survey are the first publicly available information about the scale of food insecurity in the Greater Washington region during the past year. Together, the responses underscore how the long-standing inequities across our region were exacerbated by the pandemic’s uneven economic effects.

While one-third of local households are earning more than before the public health crisis began, two in three have seen their income remain flat or decline – creating a substantial short-term strain as the cost of food and other necessities have skyrocketed, and the potential for lingering financial effects in the absences of broad action to address inequities.

This year’s analysis is the third Hunger Report conducted by CAFB, following reports in 2020 and 2021. But it is the first in which the food bank has partnered with NORC, one of the largest and most trusted independent social research organizations in the United States. The result is a survey of nearly 4,000 residents across our region, which offers the most detailed look to date at the prevalence and underlying factors of food insecurity locally. (Read more here on how the survey was conducted.)

Due to differences in methodology, these data cannot be accurately compared to previous studies on regional food security. However, the findings clearly show food insecurity to be much more widespread across the region than previously understood.

Below is a recap of the report’s key findings, as well as recommendations for ways to create greater food security and economic stability for more people in our region.

Key Insights

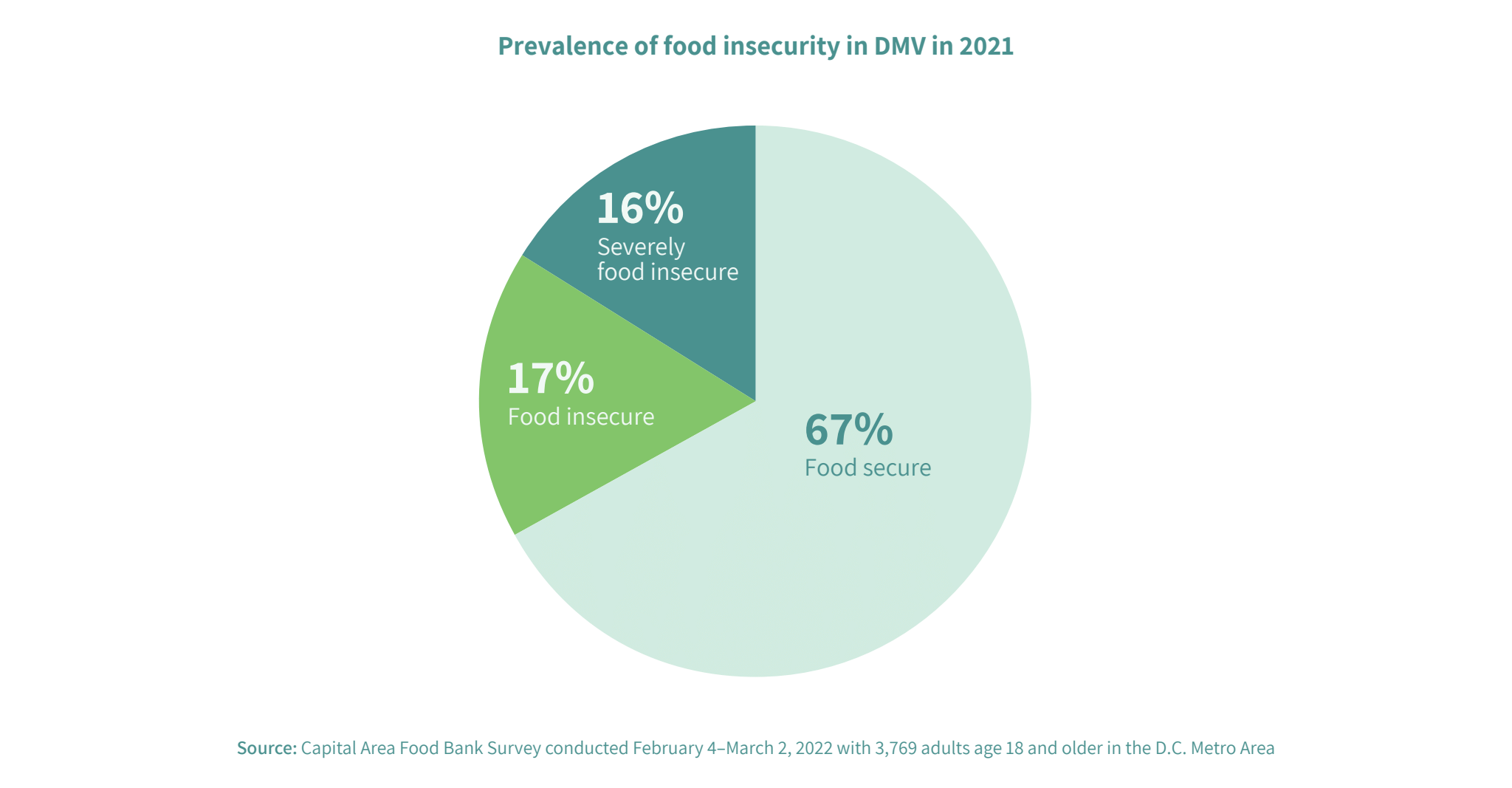

The sheer prevalence of food insecurity across the region shown in the survey results is among the most significant takeaways. Using the USDA’s standard screener, the survey found 33% of individuals across the region were food insecure at some point during the last year. Among that group, half were classified as “severely food insecure,” the most acute tier.

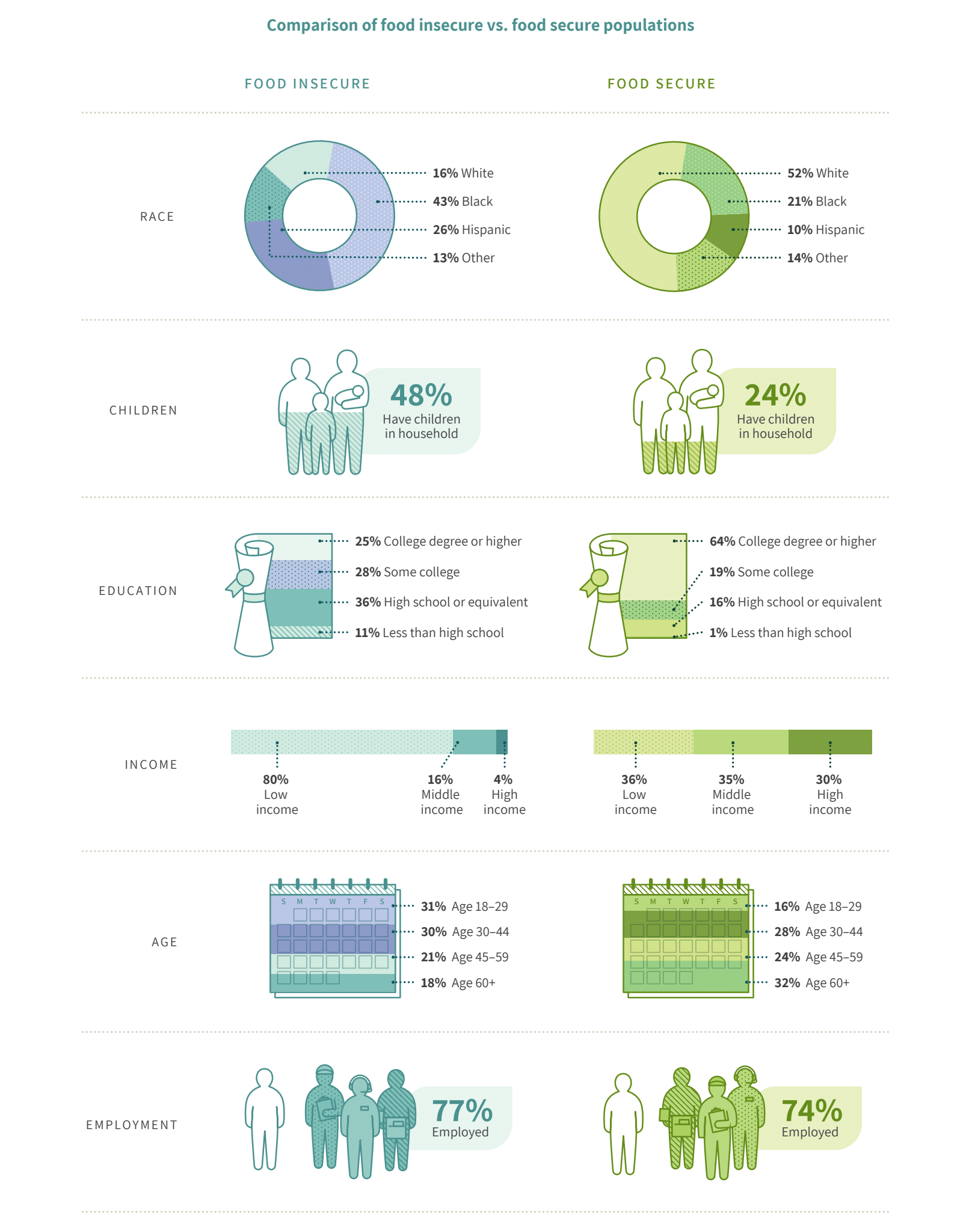

The need for greater access to food affects every community across the region, but not all communities or demographic groups are affected equally. People of color and households with kids are disproportionately affected:

- Households with children were twice as likely to experience food insecurity, compared to households without children.

- Food insecurity was much higher among those who identify as Hispanic (55%) or Black (50%) than among white respondents.

- Nearly two-thirds of households of color with children were affected by food insecurity.

Young adults aged 18–29 also are overrepresented among those who are food insecure: they accounted for 31% of the population experiencing food insecurity, despite totaling 21% of the general population.

Employment rates are essentially equal between the food insecure and the food secure.

People experiencing food insecurity are employed at the same rate as those who face challenges accessing enough food: 77% of people facing food insecurity were employed, compared to 74% of those who did not experience food insecurity.

- Among those who are food secure, nearly two-thirds have a college degree.

- Among those who are food insecure, 36% had a high-school degree or the equivalent, 28% had some college, 25% had a college degree or above, and 11% had less than a high-school degree.

Those hit hardest by the pandemic are still struggling to recover

A third of our region is earning less than they were in March 2020. Food-insecure people are significantly overrepresented in this group.

- Nearly half of food-insecure adults said that their household income is lower than what it was in March 2020. Among food-secure adults, only 18% said the same.

- 71% of food-insecure individuals said employment hardships – such as reduced hours, reduced wages, or being laid off — had a major impact on their lives. Of those not facing food insecurity, only 26% said the same.

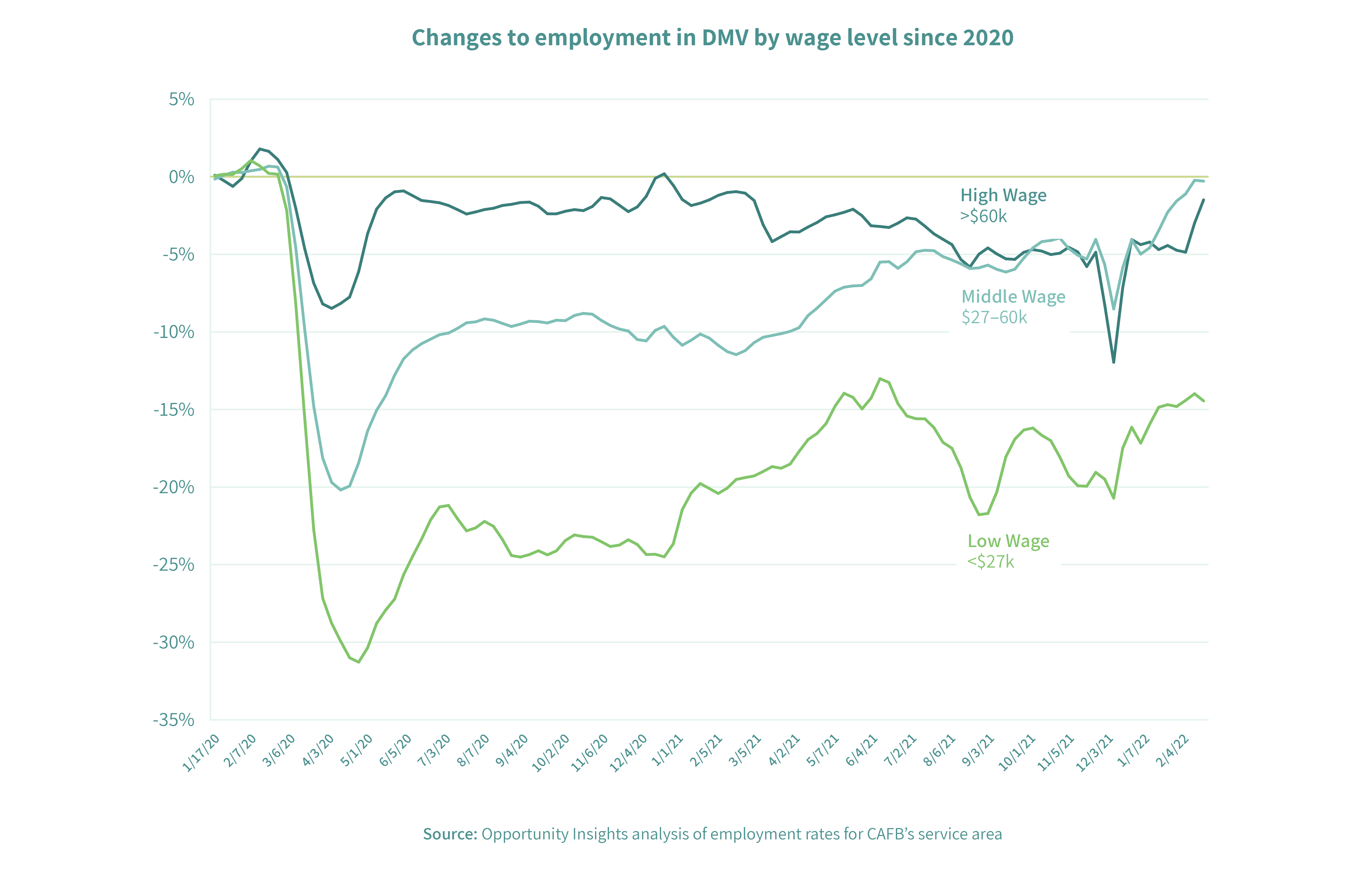

- Employment rates are still 15% lower for those who work in low-wage jobs, while employment rates for those who work in middle- and high-wage jobs have essentially returned to their pre-pandemic levels.

Divergent views on economic recovery, scale of food insecurity

When asked about their own projections of whether their household finances would improve or worsen over the next year, most people across the region are not optimistic.

- Food-insecure respondents were more than twice as likely to predict a decline in their household finances during the next year.

- Only 54% of food-secure respondents think food insecurity is currently a major problem in the D.C. metro area—with 36% considering it a minor issue and 9% believing it not a problem at all.

Most adults agree that governments of all levels bear the largest responsibility for addressing food insecurity in the United States. However, nonprofit organizations are seen as the agencies doing the most to address food insecurity.

Key recommendations

The study’s findings indicate there is still a major gap in access to high-quality employment opportunities. More than half of food-insecure adults would experience a major positive impact on their household finances from gaining access to higher-quality jobs, according to the survey findings.

- Areas for focus within the private sector include paying living wages, offering paid leave, and investing in the upward mobility of low-wage earners.

- The public sector should work to enhance the reach of income-based tax credits, and to expand eligibility and use of social safety net programs

- The social sector must find new ways to combine services in one physical location, which can reduce the logistical burden for those seeking access to assistance.

The food bank has a series of pilot initiatives based on this final concept. Known as “Food+” programs, the food bank partners with hospitals and clinics, colleges and universities, and other social service organizations to pair food access with existing programs focused on health care, education and workforce development.

The data are clear: inequity has grown during the pandemic, and the valley between the realities of those at different income levels is set to continue widening. What is needed now are accelerated efforts to address those expanding inequities.